The title idiom of this post is an apt description when it comes to the wild world of collecting World War One photography, and especially portrait/studio shots.

More than meets the eye: A hidden significance, greater than is first apparent, as in This agreement involves more than meets the eye. [Mid-1800s]

The hidden significance, as stated in McGraw Hill’s Diction of American Idioms is what makes pursuing,collecting and sharing “lost” photos from the world wars so interesting and important to researchers. The individual men and women who lived and breathed the history of our past are often presented as watered-down versions of the average Joe or Jill of their time period. By finding, researching and publishing these photos, I hope to help the public realize that every story is worth telling, irregardless of perceived heroism involved. In the case of this blog post, I’ve decided to pick a current (May 31st, 2017) eBay auction that will certainly meet the criteria of the Mid-1800s idiom seen above.

May/June 2017 eBay Auction

I will post auction details at the conclusion of this blog post, but I wanted to start with a breakdown of why this photograph will sell for hundreds of dollars more than a normal, unidentified U.S. soldier/Marine/sailor from WWI. First, lets see some of the auction details (the seller did a great job of pointing all these out and deserves credit for his research!) that make this a 10/10 snag for the lucky bidder.

What makes this a 10/10 photo for the WWI portrait collector?

- Photo aesthetics – The young man in the French studio photo (Carte Postale postcards are French) is striking a casual pose with the intention of showing off multiple pieces of his uniform/accessories. He’s sporting a bold eagle/globe/anchor (EGA) insignia on his cap, a very nice privately purchased trench watch on his left hand (indicating that he’s right handed), an overseas chevron, wound chevron and a nice set of sergeant stripes on his right sleeve.

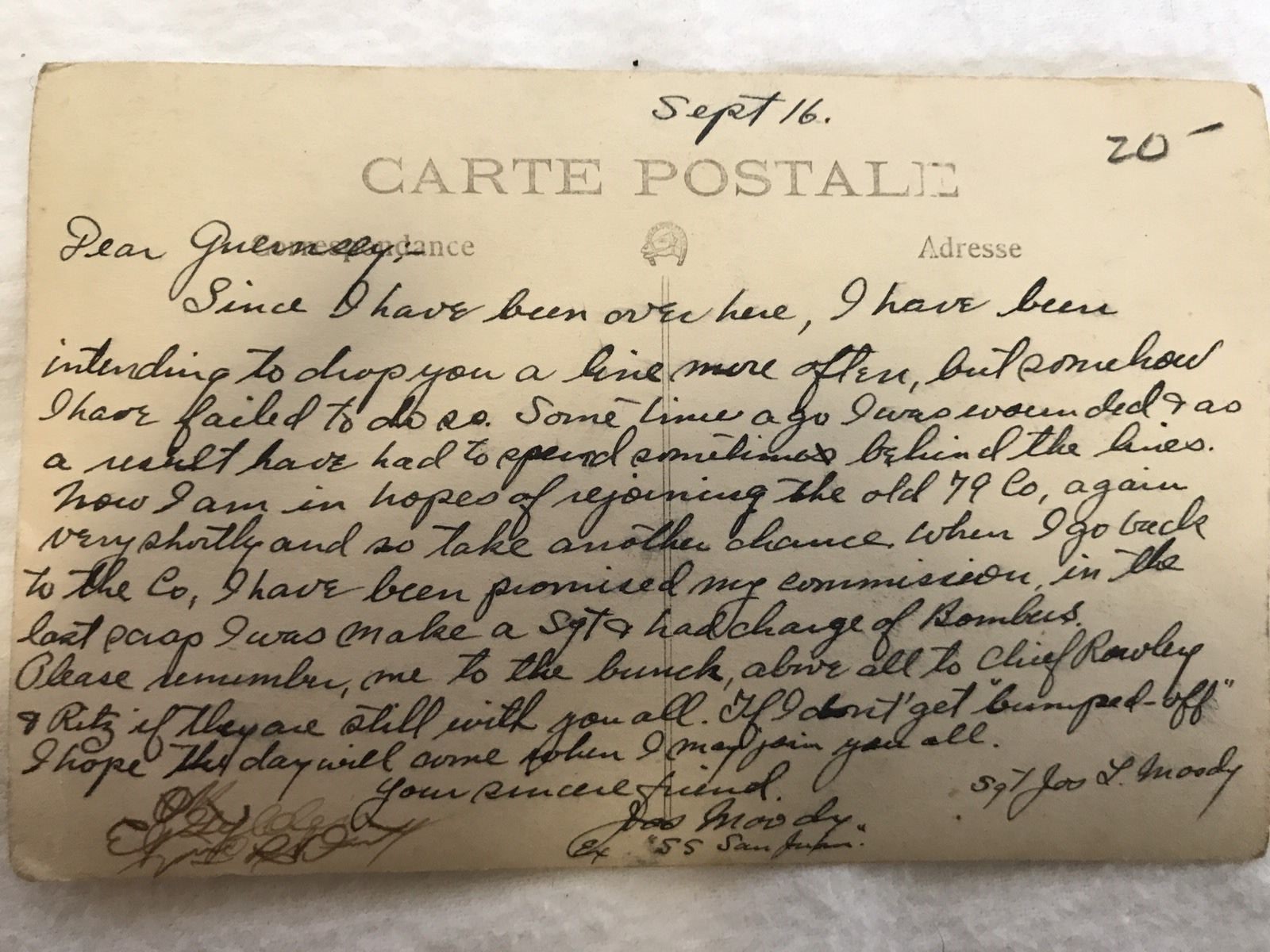

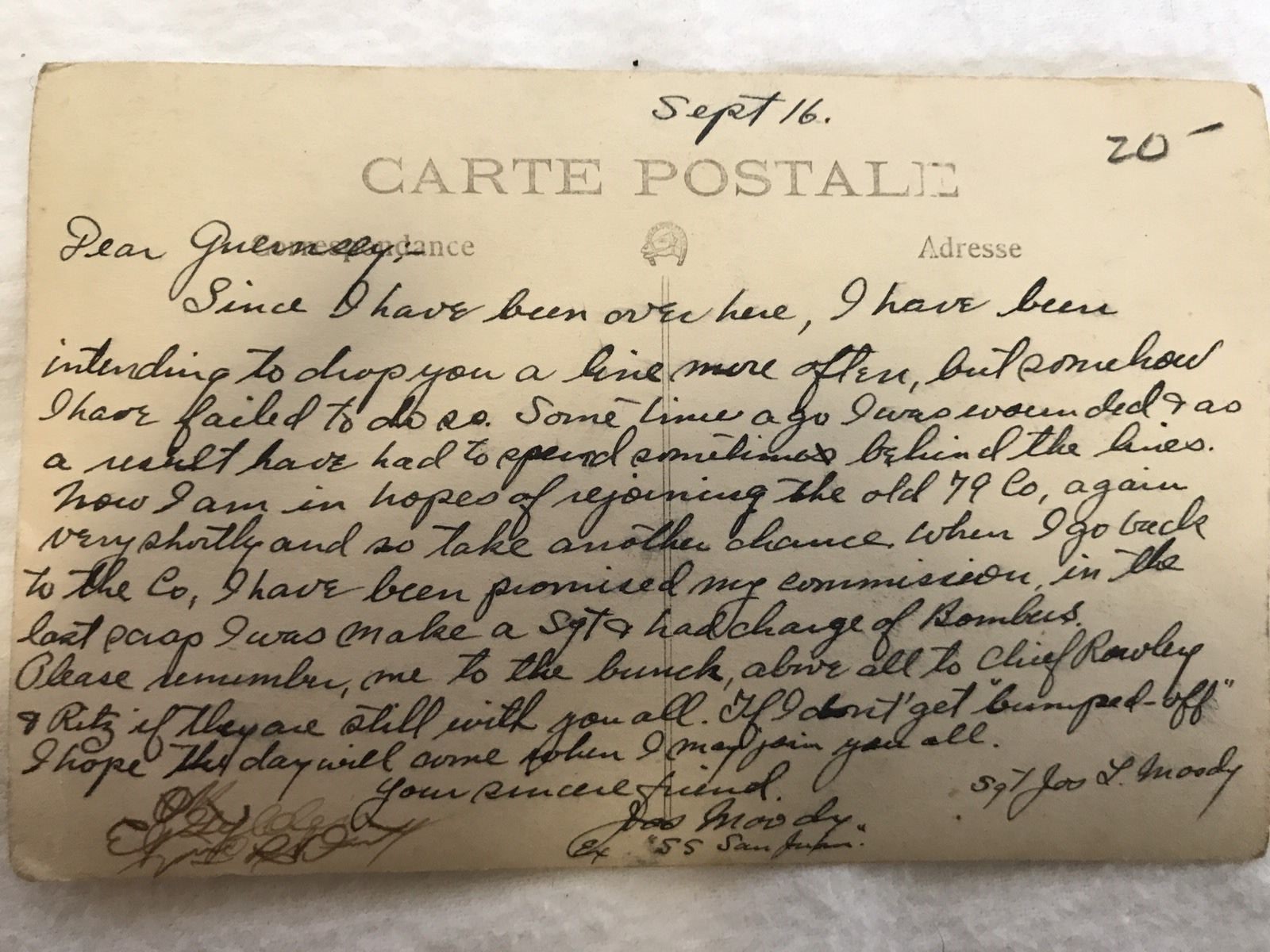

- Identification – The period inked identification on the bottom right hand corner gives the intrepid researcher a good place to start searching. I own dozens of shots signed in the same manner. Jos L Moody 6th Marines, ex “SS San Juan” is a good jumping off place…

- Written content – The back of the postcard gives a vivid description of his service time to a friend who he appears to have some strong connection to. He mentions the occasion of his wounding, his promotion of sergeant “I was made charge of Bombers” as well as an ominous mention of being “bumped off” as well as his pending commission. Further, the reverse tells us that the photo was taken and sent at least two months before the end of the war, being dated September of 1918, and therefor raises it a few notches in desirability.

- Research! – The most vital piece of elevating the significance of a photograph is the story behind the photo. What do all the other key elements tell you? In this case we have, with further research, a photograph of a U.S. Marine who was awarded the Silver Star for his actions at Chateat-Thierry. His Silver Star valor award reads:

By direction of the President, under the provisions of the act of Congress approved July 9, 1918 (Bul. No. 43, W.D., 1918), Corporal Joseph L. Moody, Jr. (MCSN: 92820), United States Marine Corps, is cited by the Commanding General, SECOND Division, American Expeditionary Forces, for gallantry in action and a silver star may be placed upon the ribbon of the Victory Medals awarded him. Corporal Moody distinguished himself while serving with the 79th Company, Sixth Regiment (Marines), 2d Division, American Expeditionary Forces at Chateau-Thierry, France, 6 June – 10 July 1918

Additionally, he is further mentioned in the unit history for the 6th Marines and some additional info can be gleaned: “The six men above {Moody included} named delivered messages through intense machine gun fire from the front line to their battalion commanders , going and returning with important messages…”

Postcard back (officer censured)

So where does this leave us? I’ve pointed out all the salient points that make an interesting photo. But my observations don’t need to be valued in any specific way. I enjoy collecting extraordinarily interesting portraits that don’t need to include identification or a “cool story”. On the flip side, a junky shot of a well-identified soldier/Marine/sailor with a cool history won’t make me open my wallet. It’s really about what you want. Go with your gut!

Ok – so here’s my prediction based on my 10+ years of buying/selling/trading WWI portrait photos. This photograph should sell for anywhere between US $175-$275. It may go for much more if someone has Sgt. Moody’s uniform, medals or has a specific affinity for the 79th Marines. I wouldn’t be surprised if it topped $350 on a good day. Tax returns are coming in?

As of 8:00 PM Eastern Time on 5/31/2017 the bid is at $23.49. I will update the post once the auction ends.

Here’s the address for those of you who have some cash to spend! (Also, $7.75 is a crazy price for shipping!)

http://www.ebay.com/itm/WWI-US-Marine-Silver-Star-Winner-Signed-RPPC-USMC-AEF-79th-CO-2nd-Bn-6th-Mar-/182599306597?hash=item2a83c44d65:g:5LwAAOSwblZZLgWN

Gossip Column

Los Angeles Times, April 16th, 1937

FILM PRODUCER’S EX-WIFE SUES Divorce Action Filed Against Retired Officer Faith Cole MacLean Moody, ;former wife of Douglas Mac- ‘Lean, film producer, yesterday filed suit for divorce from’ Capt Joseph L. Moody, United States Marine Corps, retired, charging , incompatibility. Capt. Moody, a brother-in-law of Helen Wills Moody, tennis star, married Mrs. MacLean in Shanghai in January, 1932, while he was stationed in China as an adjutant in charge of American shore forces during the Sino-Japanese troubles. He now is in theatrical work here. The couple separated March 19, according to the complaint filed by Attorney A. S. Gold- ‘flam. There are no children.

eBay Auction Result

Surprisingly enough, my estimate on the final result of the photo sale came in slightly higher than the exact average of my original estimate of $175-$275. Well, maybe it’s not that surprising given that I’ve bid on over 1,000 WWI portrait photos in the past decade….

Here’s the result! – The photo sold for $239.50 plus shipping.

6/6/2017 Final Price