The 158th Aero Squadron and the Sinking of the SS Tuscania

On the night of February 5, 1918, the troopship SS Tuscania was steaming off the coast of Islay, Scotland, when it was struck by a torpedo fired from the German submarine UB-77. The liner was carrying over 2,000 American soldiers bound for the Western Front as part of the earliest waves of U.S. troops to join the fight in Europe.

Among those aboard were men of the 158th Aero Squadron, a newly formed Air Service unit. Organized in late 1917, the squadron was composed largely of young Americans who had trained in Texas before embarking overseas. Their mission would be to support the burgeoning U.S. Air Service in France, a much needed element of warfare in the late stages of WWI.

When the torpedo struck, chaos erupted. Lifeboats were launched into rough seas, and the darkness made rescue operations difficult. British destroyers and local fishermen rushed to aid survivors. Despite these efforts, more than 200 soldiers and crewmen were lost, making the Tuscania the first U.S. troopship sunk in World War I.

The men of the 158th Aero Squadron were among the survivors. Shaken but determined, they eventually reached England and continued their training before heading off to France. Looking at this group portrait, it’s striking to think that every face here carries the memory of that night in the frigid waters of the North Channel. For the men of the 158th, their war began not in the skies over France, but in the dark Atlantic, clinging to lifeboats and praying for rescue.

Roy Oplinger and the 158th Aero Squadron

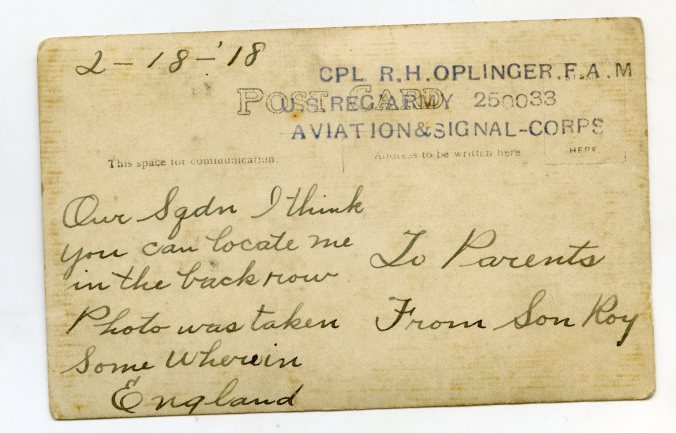

While the group photo provides us with an overall snapshot of the 158th Aero Squadron in the days after their harrowing ordeal, the photograph also highlights the wartime experience of an individual soldier who decided to send this image home to his family.

The reverse side of this English postcard has a few unique elements that help point towards the ID of the soldier who sent the postcard home in 1918. The first and obvious clue is that the photograph is likely related to someone who served with the 158th Aero Squadron. The following clues can be found on the reverse side of the postcard.

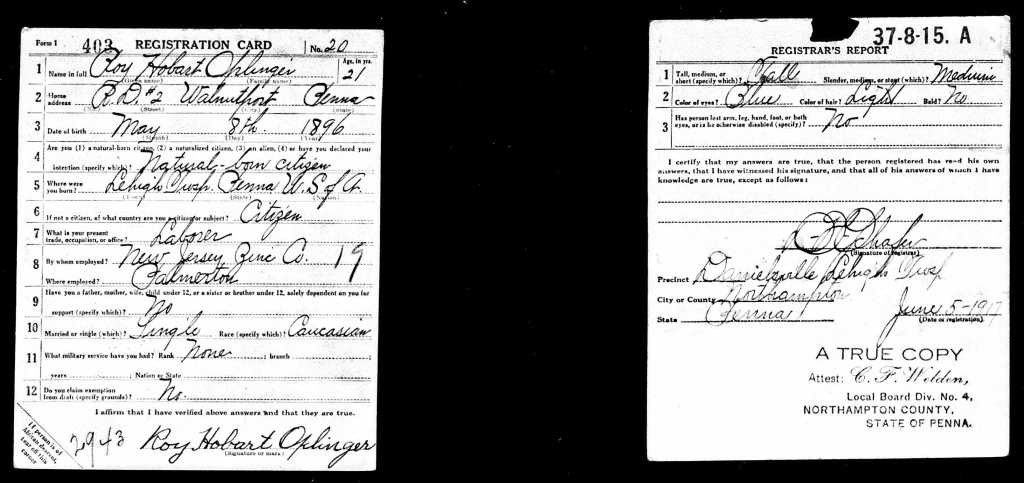

The additional clues are pretty obvious given the stamp at the top right-hand corner paired with the writing on the bottom. We know his name is Roy, and that his Army Service Number was 250033. Using the powers of ancestry.com and fold3.com I was able to identify the sender as Corporal Roy Holden Oplinger who served as a mechanic with the 158th Aero Squadron. Born on May 8th, 1896 in Danielsville, PA to Adam and Edna Oplinger, Roy went on to enlist for the draft on June 5th, 1917 with a listed address in Walnutport, PA. What doesn’t jive is that he was a private at the time of the sinking of the SS Tuscania, so it appears that he didn’t actually send this postcard to his family (if ever) until later that year when he was promoted to corporal in October.

According to Roy’s WWI Pennsylvania Veteran’s Compensation Application, after enlistment he went on to serve with the 49th Aero Squadron (an obscure pursuit squadron) in August of the same year and then on January 8th of 1918 with the 158th Aero Squadron shortly before his departure aboard the SS Tuscania.

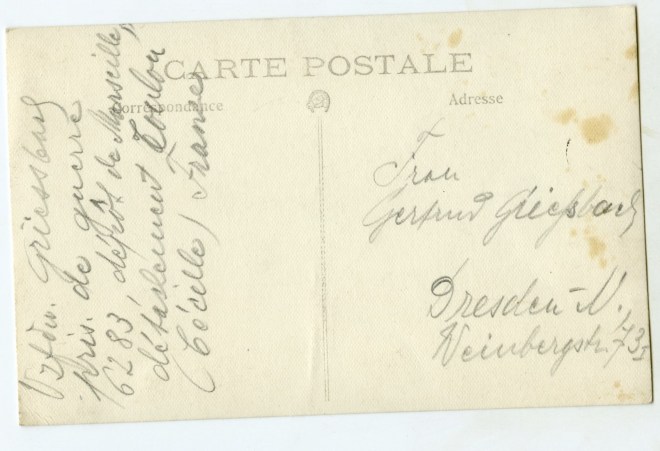

A Letter Home to a Friend

In a rare stroke of luck, I struck photo researcher gold after searching for newspaper articles related to Roy’s WWI service. In this case, it looks like he sent a letter home to a close hometown friend, Samuel W. Danner on February 13th, 1918 only a few days before the group photo was taken. Anecdotes like this offer a rare glimpse into individual moments during the war, and I was lucky to stumble across it. Here’s a link to the The Morning Call, an Allentown, PA newspaper. Please disregard any typos in the OCR transcription of the article.

Roy H. Oplinger Private in 158th Aero Squadron now in France received the following letter: American Rest Camp, Winchester, England.

February 13, 1918. Dear Sir: best of health and hope you are well I will let you know that I am in the same in America. I will let you know that I have experienced the Torpedoing of the S. S. Tuscania.

The very first ship sunk with U. S. Soldiers on board. I had a narrow escape, I was on deck when we were submarined, but was soon floating on the Atlantic waters on a raft, shortly after we were struck about one hour and a half later we were picked up by a British patrol boat.

If the ship would have sunk as quick as the Lusitania, why I think we would have perished. The S. S. Tuscania went down some hours later, she was torpedoed about supper time somewhere on the Irish coast. How many lives were lost I am unable to tell.

Only a few of our squadron The clothing and my personal belongings I had with me are all the articles I have, all the rest of my stuff is at the bottom of the sea with the Tuscania. But my gold watch which mother presented to me as a present some years ago is out of commission as the salt water did not agree with her very well. I do not like the taste of it myself, it does not feel very comfortable to be in the water this time of the year. But I was kept warm as I was the only one on the raft that knew how to handle an oar. So you see what I had to do to get away from that sinking ship.

There is danger in being too near a sinking vessel as the suction will at times suck persons down that are near. I paddled along and when rescued we eight boys on the raft were a few miles from the ship. We were somewhat soaked. But I am dry by the time you received this letter. Ha Ha.

I will never forget that shock of that torpedo which hit us on that night February 5, 1918. The boys were brave and sang national hymns when we let her go down. Every soldier was coal as jar as I know not one was panic stricken, all left that ship in an excellent manner and can tell you from my experience what I have had in seeing a ship sunk. That you can thank God if you never have to witness that kind of a sight on a rough sea. I am sure glad that I am safe.

It was God’s will that only a few lives were lost in the ship wreck. I will sure do my best to do a little harm towards “Kaiser Bill” as he has to account for the lives that were lost on that cold night (you know). I am yours as before.

Address, Priv. Roy H. Oplinger, 158th Aero Squadron. A. E. (via) N. Y.

And Some Insight From a Friend

Fast forward to 2025, here’s some information about the photo from a WWI researcher friend of mine, Charles “Chuck” Thomas. Thanks Chuck!

Chuck’s Take

Here is a special image of the surviving members of the 158th Aero Squadron shortly after arriving at the American rest camp in Winchester, England. This squadron was aboard the Tuscania when it was sunk by a German submarine off the northern coast of Ireland 5 February 1918. When the 158th AS was reassembled at Winchester, it was determined that seventeen men had been lost during the sinking. After the picture was taken, the flying officers were sent to France for training and the enlisted members were broken up into four flights: one flight was sent to Beverly, Yorkshire and the other three went to Lincolnshire, England.

The squadron would later be reunited and sent to Issoudun on 27 September to finish out their service at that aerodrome.

The squadron officers were:

1st Lt. Phil E. Davant

1st Lt. Herbert B. Bartholf

1st Lt. J. W. Blackman (Gorrells has it spelled ‘Blakcman’ – typo?)

1st Lt. Merle H. Howe

1st Lt. Miner C. Markham

2nd Lt. Kenneth S. Hall

2nd Lt. Freeman A. Ballard

2nd Lt. LaRue Smith

2nd Lt. James McFaddan

Of note is the mixture of civilian attire with military uniforms being worn by some of the enlisted men.

I should also point out that the flag seen here was the only one saved during the sinking of the Tuscania by Corp. Guy W. Burnett.