The following article was graciously submitted by Sam Pestle. To see more stories of WWI soldiers with accompanying portrait photography, please check out Sam’s page – The United States in WW1 on Facebook.

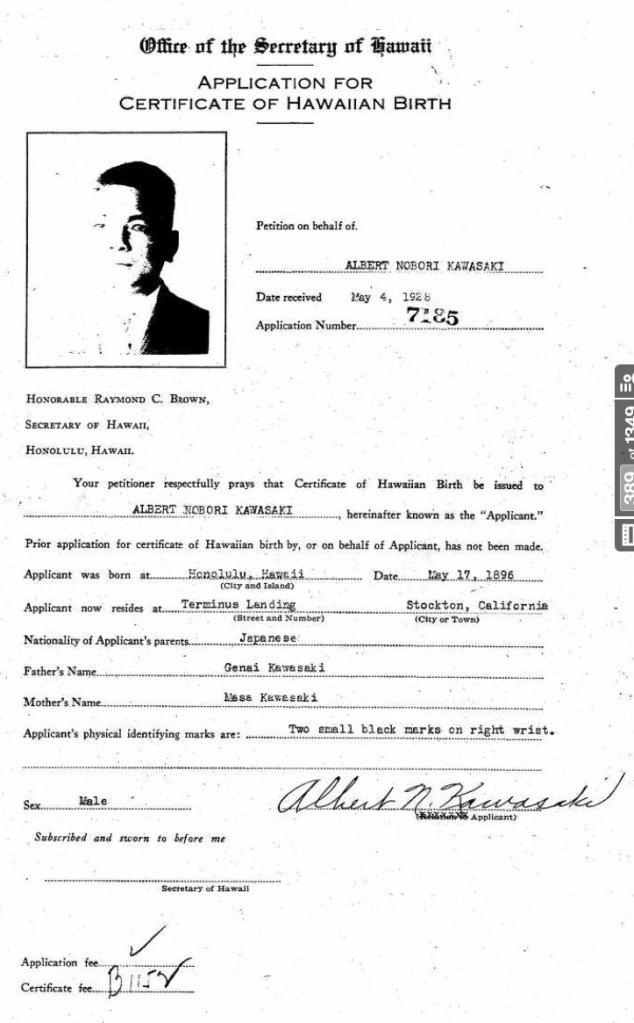

Albert Nobori Kawasaki was born in Honolulu, within the Republic of Hawaii, on May 17th, 1896. His parents were Japanese immigrants from the Hiroshima Prefecture, and government documents indicate that Albert spent six years in Japan attending school during his youth. He was bilingual in Japanese and English, and later moved to Sacramento, California (possibly in 1914). He was a student at the Sacramento High School during the 1917 draft registration and denied any deferments from military service. Albert was subsequently inducted into the US Army on March 31st, 1918, and was soon assigned as a Private First Class with the US Army Medical Corps.

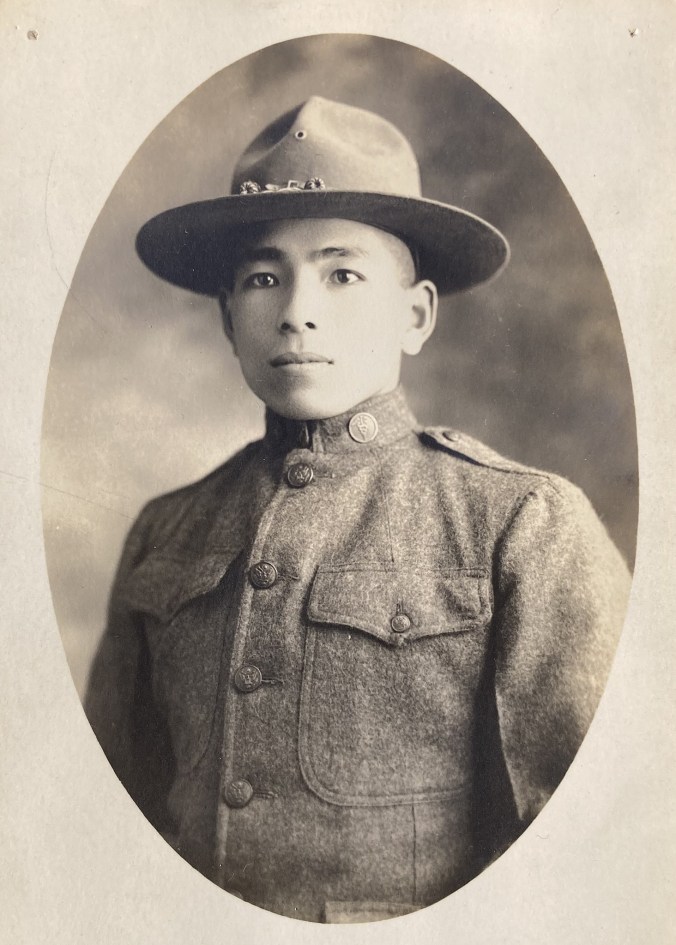

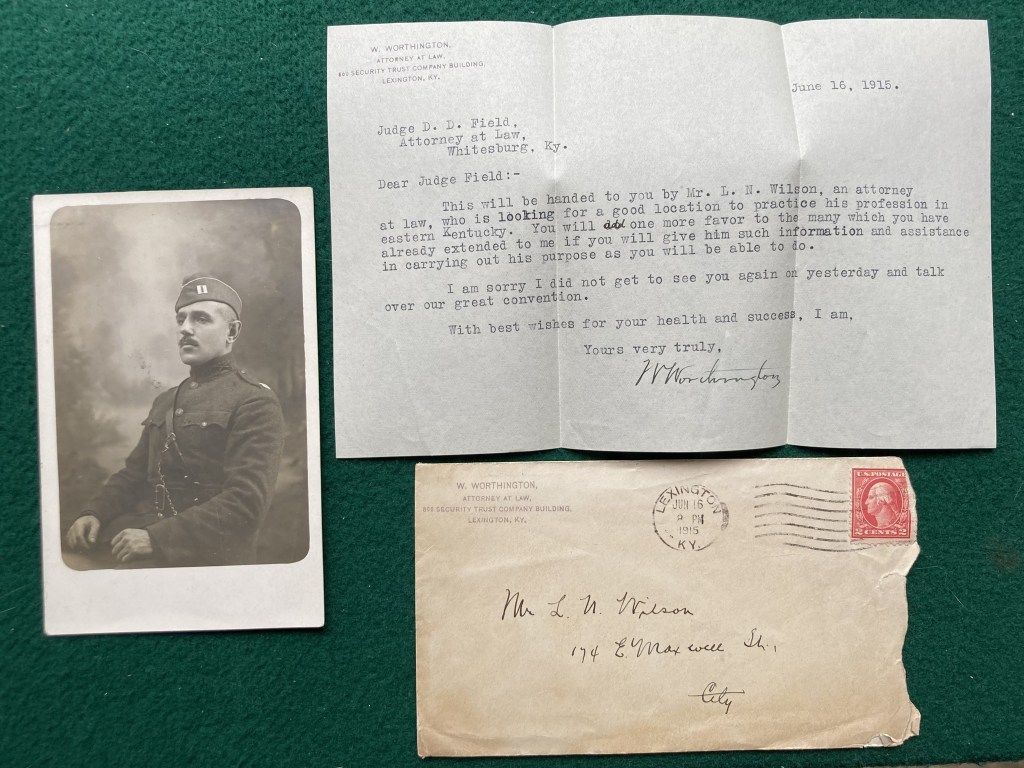

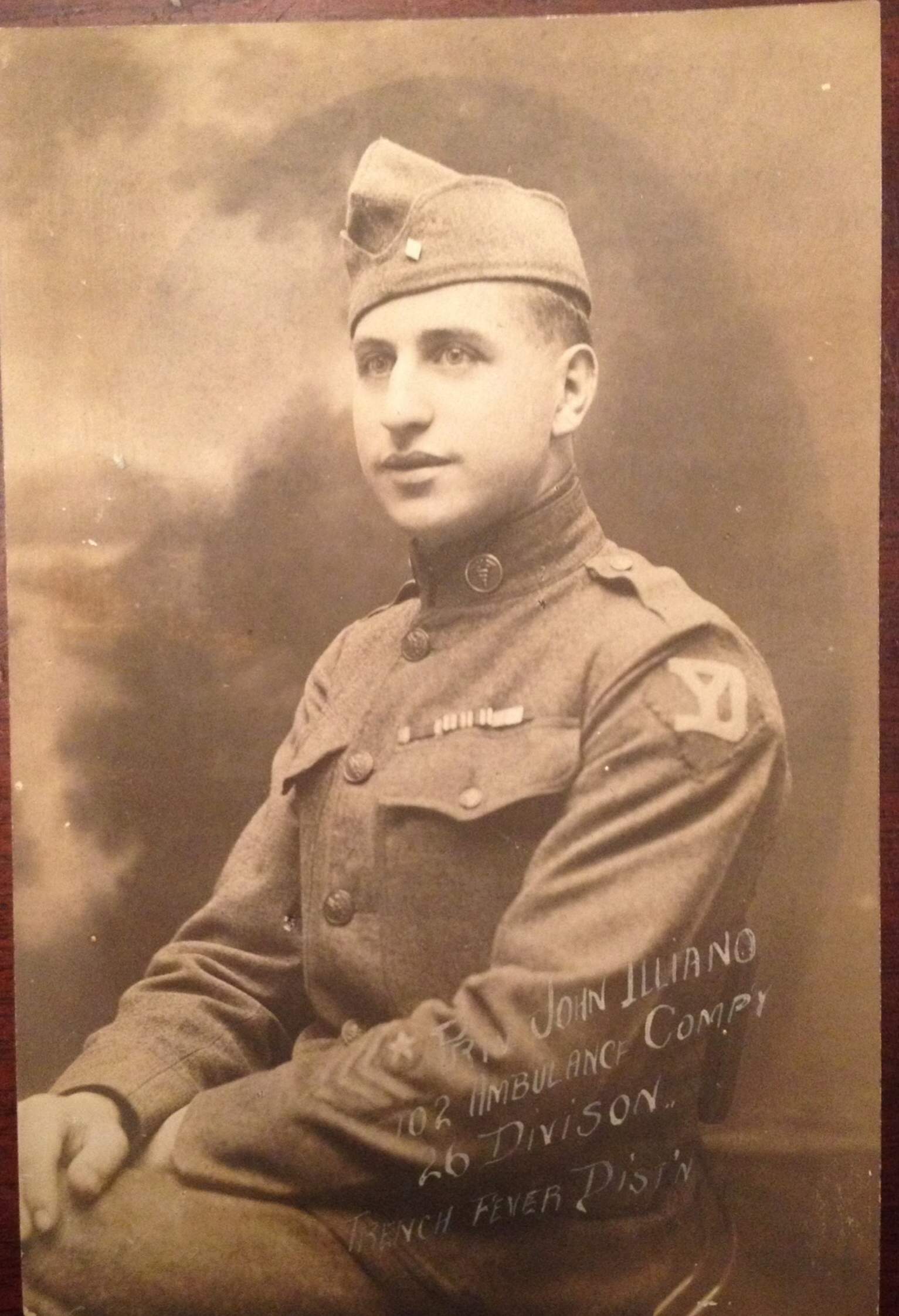

PFC Kawasaki was sent across the United States to Michigan and assigned to the Medical Detachment of the 160th Depot Brigade at Camp Custer. This photograph has a studio marking on the reverse that indicates that the image was taken at the Camp Custer photography studio. As a member of the medical corps, it seems likely that Albert was assigned to the base hospital throughout the final months of the First World War. An outbreak of Spanish Flu at the camp began in September of 1918 and left thousands of doughboys profoundly sick and requiring medical intervention. An estimated 674 soldiers died of influenza during this period, and it’s very likely that PFC Kawasaki regularly faced death throughout his military service (despite never traveling overseas for AEF service).

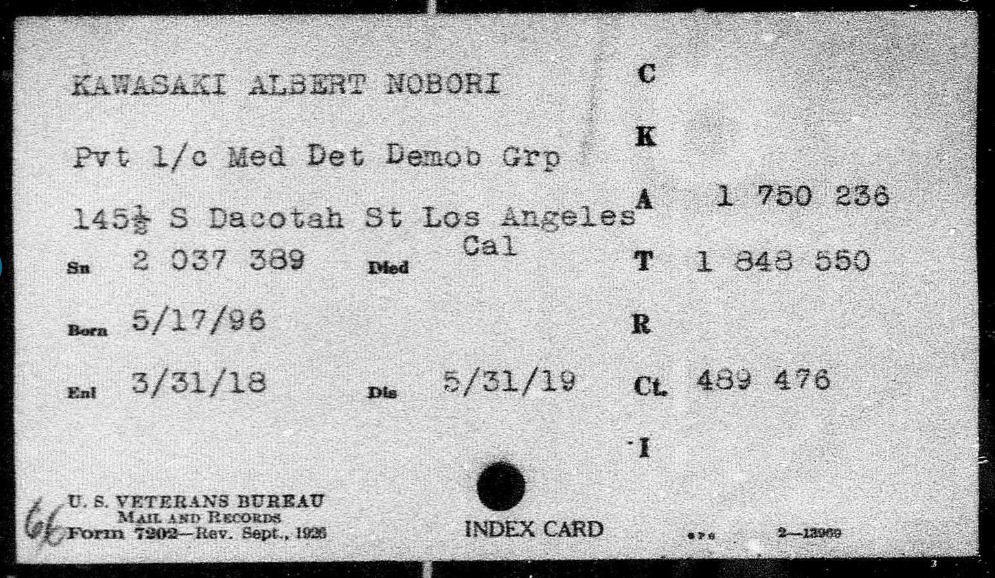

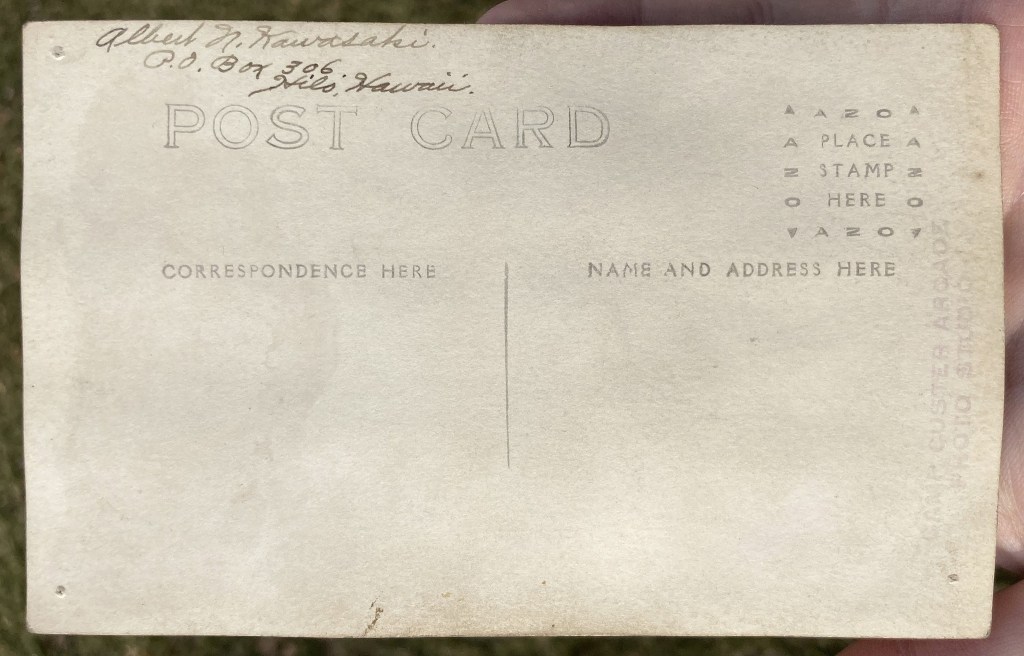

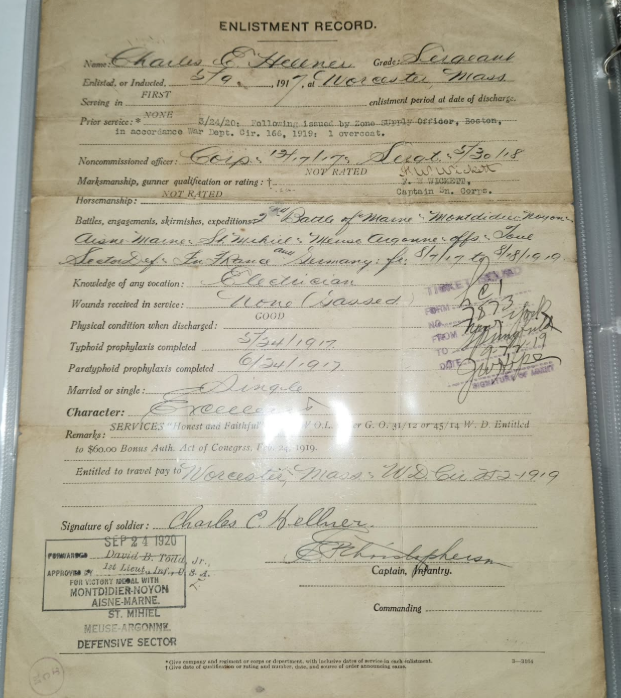

PFC Kawasaki received an honorable discharge from the army on May 31st, 1919, and his service number was 2037389. Albert subsequently sailed back to Hawaii aboard the SS Tenyo Maru in June of 1919, and I suspect he visited his aging parents in Hilo, HI. He returned to the United States four months afterward and continued his life in California. Albert was married in a Buddhist ceremony by Reverend Junjo Izumida on July 10th, 1922, and the couple soon had two sons born in 1925 and 1927.

Beginning in 1923, Albert attended classes at the University of Southern California for three years but did not graduate with a degree. He later worked as a celery farmer, agricultural foreman, and farm manager. Albert was considered a local community leader and served as the President of the Japanese American Citizen League of Stockton, California. Unfortunately, Albert also faced multiple hardships throughout his lifetime, including filing for bankruptcy in 1928 and experiencing a divorce from his wife in April of 1942.

Just months following his divorce, Albert was notified that he would be among the 125,000 Japanese Americans interned by the Federal Government during the Second World War. Despite his American citizenship and honorable service within the US military, Albert was a victim of the national paranoia and racial prejudices following the Attack on Pearl Harbor. He was initially held at the Stockton Assembly Center but was later interned in Arkansas at the Rohwer Relocation Center between October 19th, 1942, to July 19th, 1943. He was among 8500 other internees at the Rohwer Camp during this period (including a young George Takei, later of Star Trek fame).

Following his release from the camp, Albert returned to California and died just four years later at the age of 51 years on June 13th, 1947. His remains were subsequently cremated and now rest in a niche at the Inglewood Park Cemetery of Inglewood, CA.