The following article was graciously submitted by Sam Pestle. To see more stories of WWI soldiers with accompanying portrait photography, please check out Sam’s page – The United States in WW1 on Facebook.

The son of a presbyterian minister, Laurance Newton Wilson was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on January 19th, 1890. His family later relocated to Washington D.C. and Laurance graduated from high school in 1909. Laurance then chose to pursue higher education and was accepted into the Law School at George Washington University. Records indicate that he was an exceptional student at GWU and became a member of the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity. Of particular interest, future FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was also in attendance at the law school during this period, although he graduated a year after Laurance.

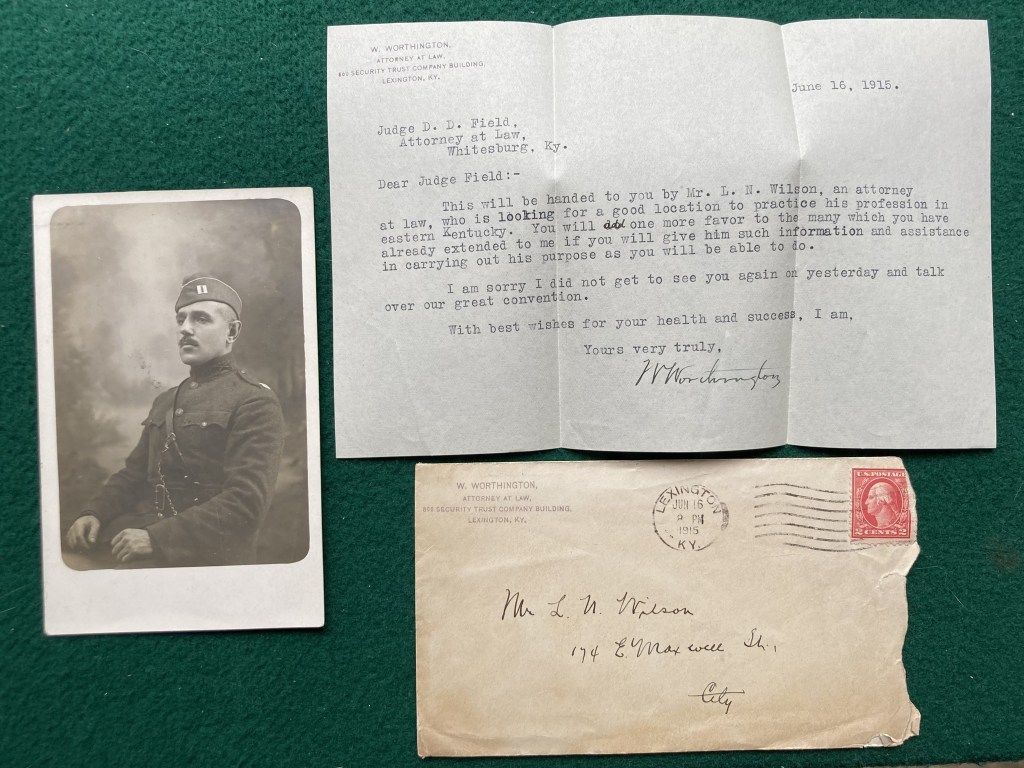

Following his graduation in 1915, Laurance passed the bar and began practicing law in Lexington, Kentucky. He had been working for less than two years when America became involved in the First World War, and Laurance applied as a candidate to the US Army Reserve Corps on May 15th, 1917. He was sent to Fort Benjamin Harrison for officer training and received a 2nd Lieutenant’s commission on August 17th.

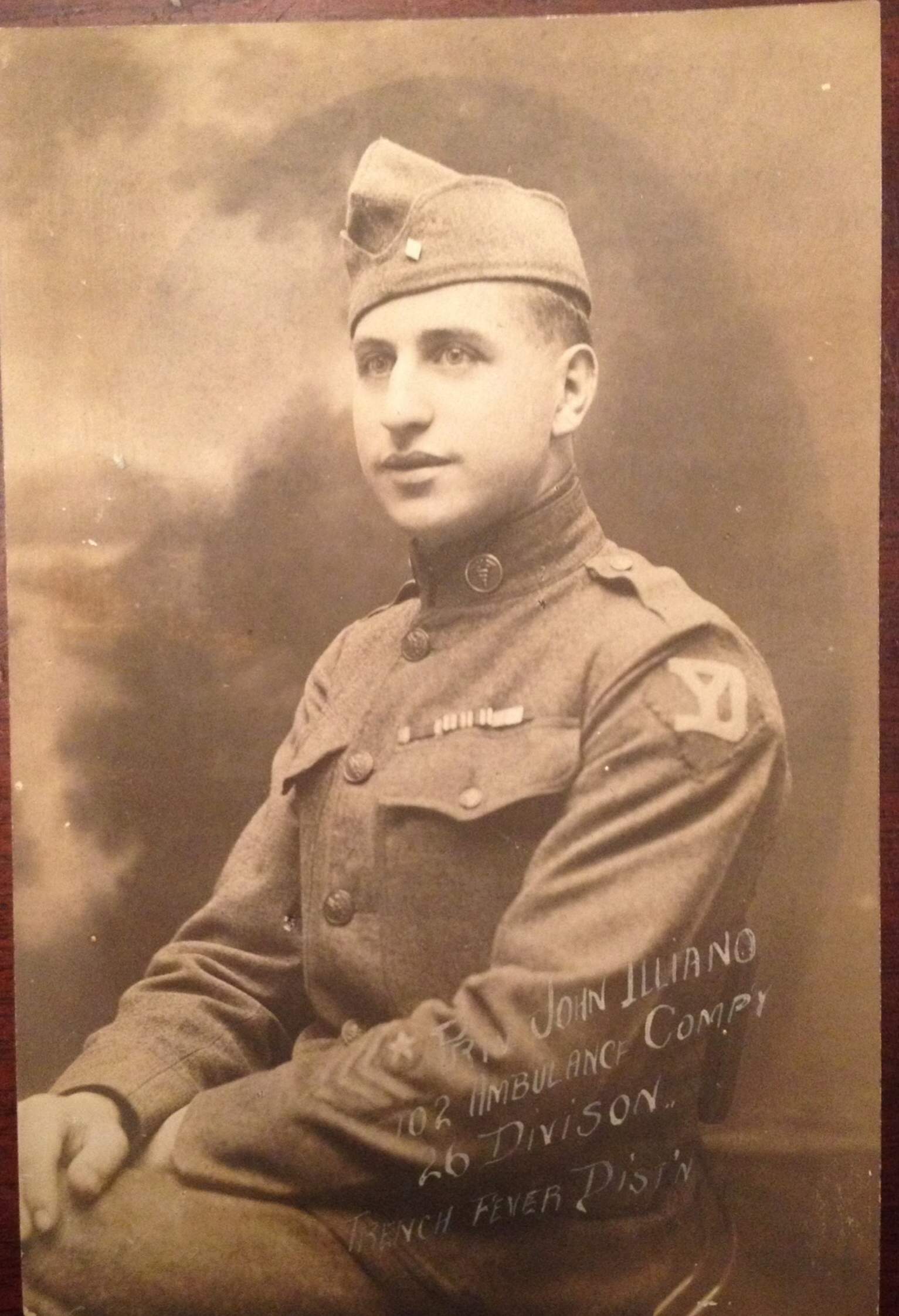

Laurance was later promoted to 1st Lieutenant and assigned to command Company “C” of the 801st Pioneer Infantry Regiment. It is important to note that this was a segregated unit of the US Army that was composed of enlisted African American doughboys commanded by white officers. The 801st Pioneers sailed to France aboard the USS Manchuria on September 8th, 1918, and arrived along the Western Front in the final weeks of the conflict. The regiment served under the American 1st Army and was assigned to battlefield salvage operations and munition disposal efforts in the Chateau-Thierry Sector (this was a hazardous job which led to several men being killed or wounded in the regiment).

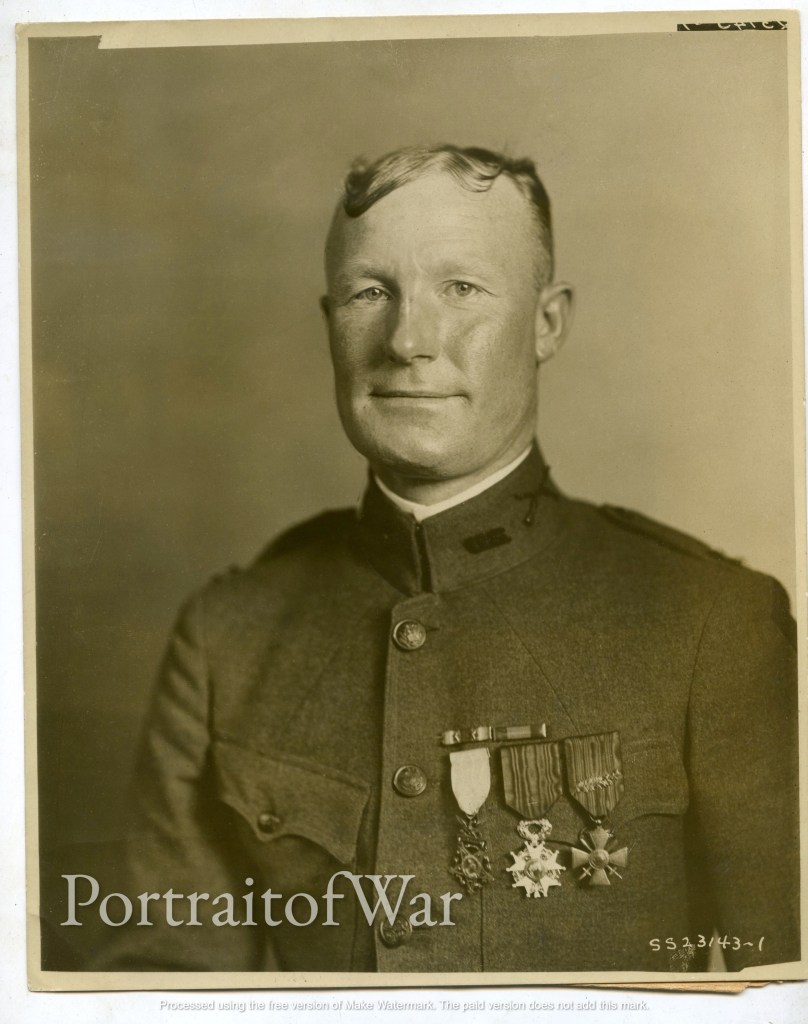

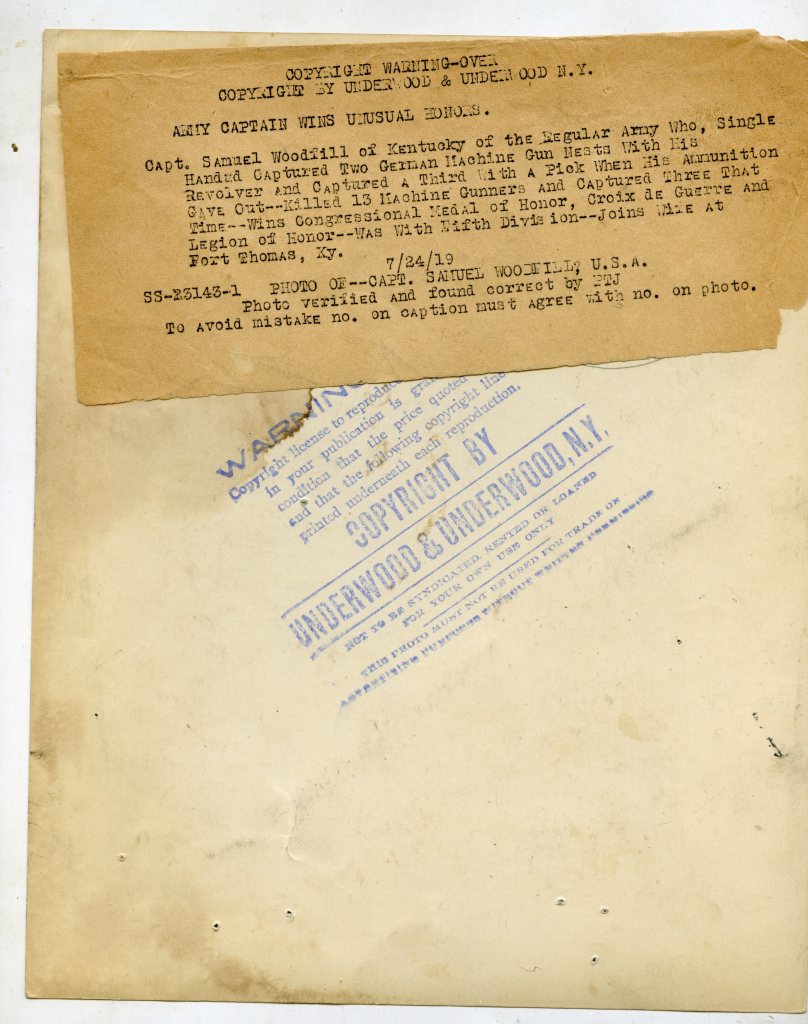

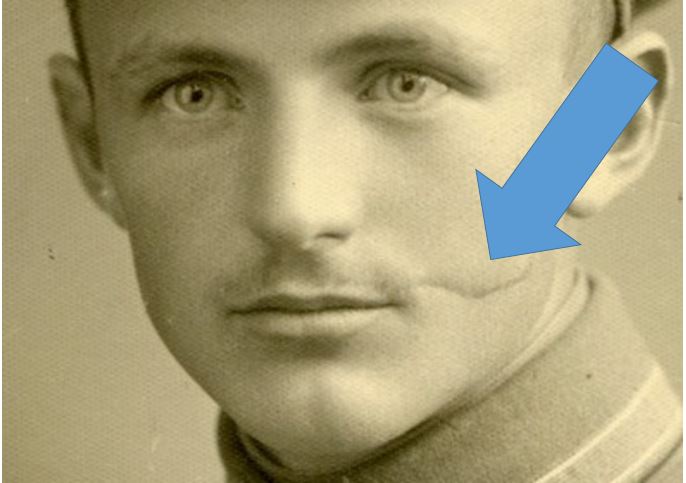

Following the November Armistice, Laurance was promoted to Captain and the French photograph seen below originates from that time period. Cpt. Wilson was then reassigned to command Company “F” of the 305th Infantry Regiment in December of 1918. He later completed his AEF experience while serving as a regimental adjutant and returned to the United States aboard the RMS Aquitania on April 24th, 1919. He received an honorable discharge on May 29th.

Laurance returned to his work as an attorney after the war and was employed by the Royal-Globe Insurance Company for several decades. He married in 1924 and lived much of his subsequent adult life in New Jersey. Laurance does not appear to have had any children and later retired to North Ferrisburgh, Vermont. He suffered a stroke in his final years and died of bronchopneumonia due to aspiration on April 26th, 1970, at the age of 80 years. He now rests beneath a civilian gravestone beside his wife in the North Ferrisburgh Cemetery of North Ferrisburgh, VT.