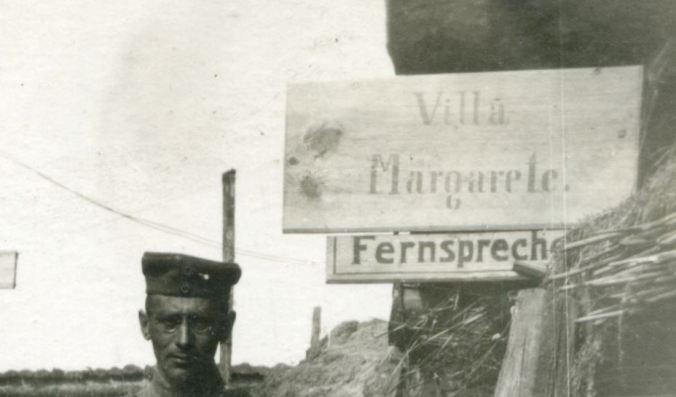

Tonight we have a guest post from a Facebook friend who also enjoys collecting WWI photography. Special thanks to James Taub for providing us with this interesting shot of a French soldier!

A Poliu of the unfortunate 111e régiment d’infanterie. During the Battle of Verdun, on 20 March, 1916 the 111e was in positions in the woods near Malancourt and Avocourt. (Later to be crucial points during the 1918 Meuse-Argonne Offensive.) They suffered under an intense German bombardment before being assaulted by flame throwers. The four German regiments from Bavaria and Wurttemberg infiltrated deep into the 111e’s position. The regimental commander, the colors the JMO (war diary), and 1,200 other officers and men were lost, many taken prisoner. The Germans used the capture of the 111e as propaganda, and the French Army responded by disbanding the regiment and accusing all 13 companies of treason. One French official even stated that “the uninjured prisoners before the end of the war be worked into a court-martial “. It would not be until the late 1920s that it was admitted by General Petain that the regiment was one of the many sacrificed to slow down the German assault. In 1929 the 111e was reformed, and their colors allowed to hang in Les Invalides

Capitaine Jean Nardou of the 111e wrote:

“A 7h00, un bombardement très violent commence (grosses torpilles et engins de tranchées de toutes sortes) sur nos tranchées de première série et petits postes ; obus de gros calibres sur les deuxième séries et boyaux.

Vers 9h00 j’envoie à mon chef de bataillon la communication suivante par un planton : “Les tranchées sont détruites, les abris démolis ou bouchés ; le téléphone, le bureau sont en miettes, la poudrerie a sauté, mes papiers sont détruits, la situation me paraît très critique”. Le bombardement a continué avec une intensité de plus en plus grande et est devenu d’une violence inouïe après 15h00. A partir de ce moment , tout mouvement dans les tranchées et boyaux était impossible, tant le bombardement était grand. Un peu avant 16h00, les Allemands ont lancé des liquides enflammés sur plusieurs petits postes qu’ils ont également fait sauter à la mine et ont profité de la fumée noire et épaisse qui se dégageait pour s’approcher de nos tranchées qu’ils ont attaquées de revers et de face à l’aide de grenades, pendant que leur bombardement continuait.”

“At 7:00 am, a very violent bombardment begins (big mortars bombs and trench machines of all kinds) on our first series trenches and small posts; shells of large caliber on the second series and dugouts.

Around 9:00 am I send the following communication to my battalion commander: “The trenches are destroyed, the shelters demolished or plugged, the telephone, the office are in pieces, the blowing snow has blown up, my papers are destroyed, the situation seems to me very critical “. The bombing continued with increasing intensity and became incredible violence after 15:00. From that moment, any movement in the trenches and dugouts was impossible, so much was the bombing. A little before 4 pm, the Germans fired flamethrowers on several small posts that they also blew up at the mine and took advantage of the thick black smoke that was emerging to approach our trenches they attacked. from behind and from the front with grenades, while their bombardment continued.”

French Poliu of the 111th Infantry Regiment