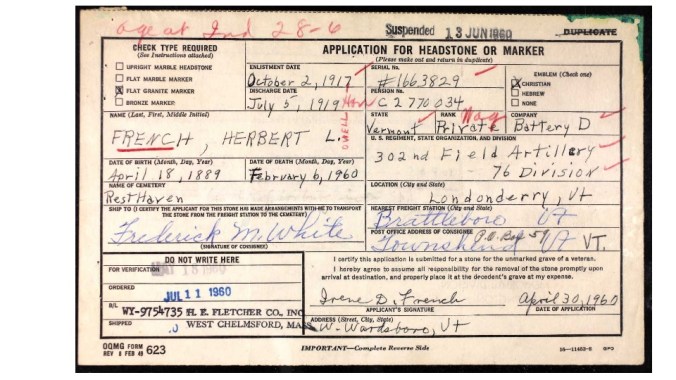

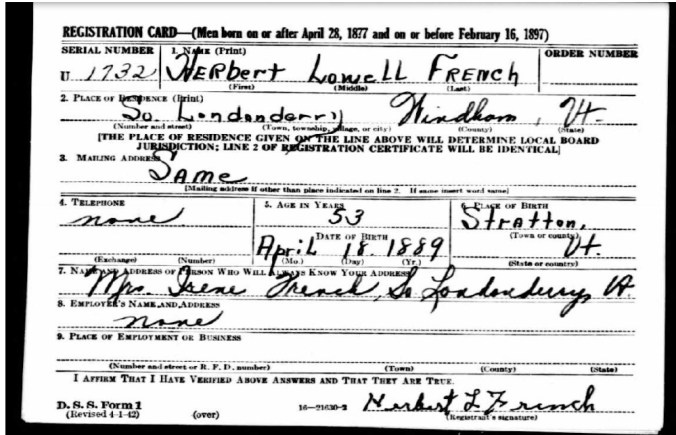

WWI Photos of Vermonters are hard to find and I continually search for superlative examples at flea markets and yard sales. This past May I was lucky enough to encounter a Vermonter dealer at a Massachusetts flea market. Low and behold, the seller had a fantastic image of a WWI Vermonter for sale! Herbert L. French is identified as being from Stratton, VT and as being a member of the 307th Field Artillery of the 78th Division.

Collecting

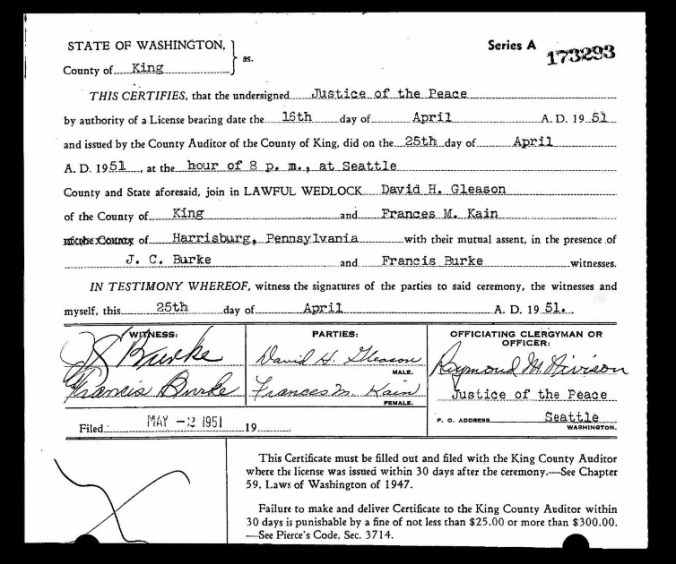

WWII American Nurse Corps Overseas Cap Identified – Lt. Frances M. Gleason of Washington

From here I was able to confirm my hunch that she was the owner of the cap. Her obituary and grave record show that she was a WWII veteran who served in the ETO as a Lt. in the Army Nurse Corps.

Grave Photo

Courtesy of FindaGrave.com

Frances M. Gleason, age 90, passed away August 14, 2009 in Mount Vernon, WA.

She is survived by daughter, Beverly (Dr. Marshall) Anderson of Camano Island; and grandson Kristopher Anderson of Arlington.

She was a World War II Veteran of the Army Nurse Corp. serving in the U.S and European Theater. She worked as a nursing instructor for the Practical Nursing Program at Columbia Basin Community College in Pasco for 21 years.

At her request no public services will be held.

Arrangements are under the care of Hawthorne Funeral Home, Mount Vernon.

WWII Photo Grouping – Men of the 31st Signal Company, 31st “Dixie” Division Portrait Photos

One of my favorite neighbors growing up was a member of the 31st Dixie Division and always took time to tell me about his experiences during the war. As I grew older, he told me some of the more intense stories of his time on Mindanao and of his being wounded while attacking a Japanese airport. Those memories have always stuck with me, and with those memories come an attachment to photographs from the 31st Division. It’s one of the hardest divisions to find on eBay and I was especially excited to find this set of 8 images listed as “(8) Vintage WWII photos / Happy American GI Soldiers with Names – Old Snapshots”.

My WWII patch radar went off when I recognized a portion of a 31st Division patch in one of the shots. I did quick searches on each of the soldiers and found a website for Mr. Fred B. Kearney of Kokomo, Indiana. The name matched with the town on the reverse of the photo and the writeup mentioned his service with the 31st Signal Company of the 31st Division during WWII. Bingo, my hunch was correct that this group was a portrait collection of soldiers of the Dixie Division.

Company members identified in the images include:

Fred Kearney of Kokomo, Indiana

Jack Parsons of 905 Kramer Ave, Lawrenceburg, TN

Joseph Kalmiski (sp) of 26 Willow Street, Plymouth, PA

“Shaw” of 220 N. Lewis Street, Staunton, VA

Merrell Warren of Box 84 Bowdon, GA

Eugene W. Carroll (identified through draft records) of 3140 Long Blvd., Nashville, TN

WWI Photo: Research Uncovers 33rd Division Veteran’s Identification! 130th Infantry Regiment Wounded!

Sometimes it takes a good bit of time to lock down the identity of the sitter in a photograph. I wouldn’t be able to do it without the help of dozens of research friends and an equal number of archive websites. With that said, I was able to purchase, research and identify and post a positive identification of a recent eBay purchase! It’s not an easy endeavor, but it’s something that will be worthwhile at some point in the future.

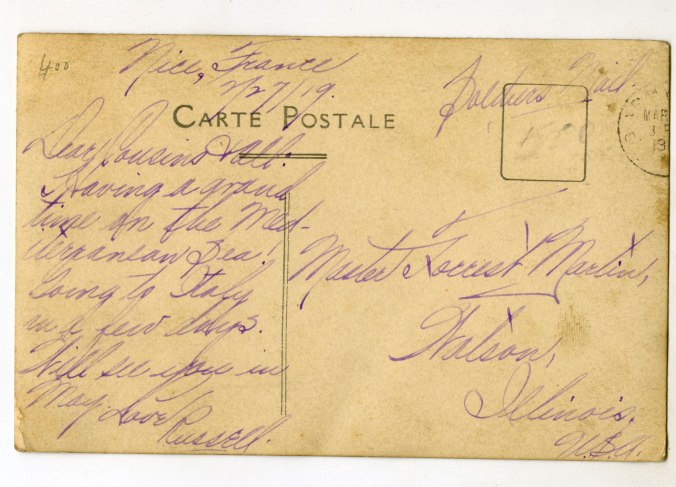

What are we working with for an identification? The soldier has a definite first name of Russell and is cousins with a male named Forrest Martin of Watson, Illionois in 1919. Given the intro and body wording, he’s likely to be close to the recipient.

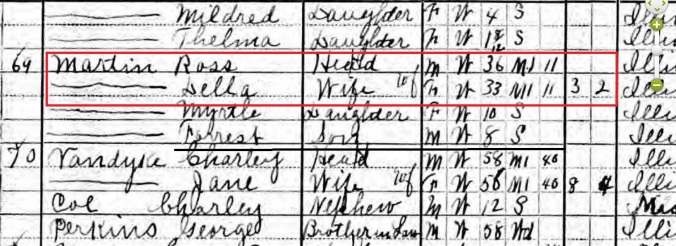

I started by researching the recipient, Forrest Martin, and found his 1900 census entry:

From here I decided to research his mother and father in search of a series of siblings to track down as aunts and uncles to Russell. An aunt or uncle would produce a cousin which should provide me with the proper identification for the 33rd Division soldier!

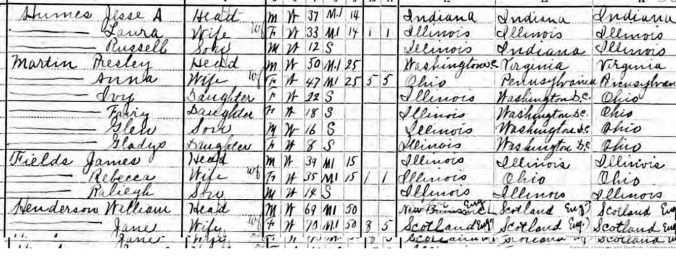

After over an hour of searching (tiring for sure) I was able to identify his mother’s sister as a Laura A. Humes. Laura had a son named Russell in 1897! When I clicked on his military burial record it all came together. Please keep in mind that this took hours of research!

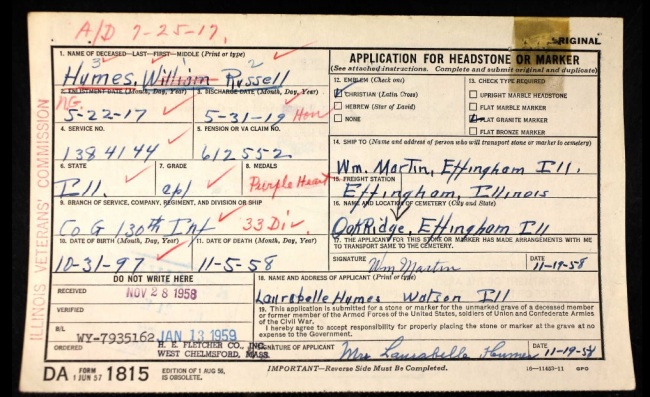

Russell Humes, first cousin of Forrest Humes (recipient of the postcard), was in Company G of the 130th Infantry Regiment of the 33rd Division in WWI. He achieved the rank of Corporal and was wounded in action at some point during his service. His portrait photo was taken in 1919 long after his wounding. He passed away on 11-5-1957 at the age of 61.

WWI Dog Tag Identified: Ancestry.com Research Discovery – WWI Ohio Veteran Identified

Dog tags and identified material are easily collected by militaria enthusiasts due to the personal connections with names, families and units/divisions. Collecting dog tags is an easy way to feel a connection with the past; many dog tags were actually worn during combat and followed a soldier across the European continent. In this case I was able to pick up a cheap (less than $5) dog tag on eBay. A quick search for Charles L. Fox Brought up a smattering of possible leads that crisscrossed the country. Census records and marriages were of no help. I spent over an hour searching through military records for a man named Charles Fox born between 1885 and 1899 (a generally good search range for WWI veterans) and landed a solid hit. It’s not often that I identify a veteran through his/her serial number, but I was able to ID Charles L. Fox as having been born on December 14th, 1889 in Whitehouse, Ohio. He served with an ordnance supply unit in France during the war and was honorably discharged on July 26th, 1919. I was lucky to find both the veteran headstone marker card as well as the state veteran roll. A fun find, and another reason to invest in an ancestry.com account!

Forestry Engineers of WWI: The Unsung Heroes of the 20th Engineer Regiment

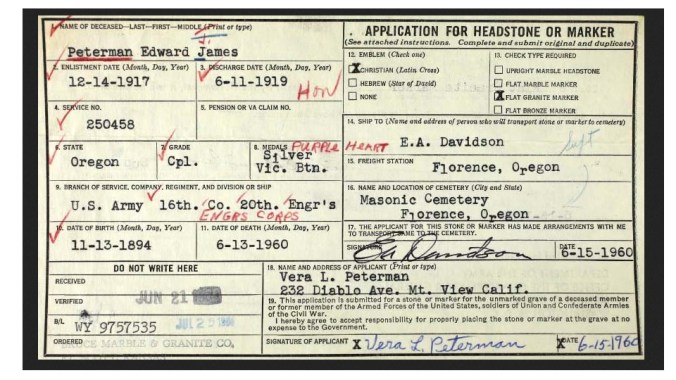

My interest in the forestry units of WWI started with an inexpensive eBay purchase back in 2012. I was lucky enough to pick up a copy of the 20th Engineer Regiment’s unit history from WWI. This particular copy had been in a fire at one point in it’s long life and was luckily only singed on the corners. The burned edges and soiled pages give the book a feeling of age and rugged dignity. The inside cover in inscribed by an Ed. Peterman of Florence, OR who was assigned to the 6th Battalion of the 20th Engineers.

In an incredible stroke of luck I was able to find a 1920s photo of Mr.Peterman on ancestry.com. Ed was born in Winona, MN on November 13th, 1894 and later moved to Oregon, where he signed up with the forestry engineers. According to his gravestone, he served with both the 6th Battalion, 20th engineers until 10/1918 and then transferred to the 18th Company in October of 1918. He is listed as being a corporal and was wounded by enemy action, which is very rare for a forestry engineer. Ed was also a distinguished member of a very exclusive club. He was on board the S.S. Tuscania when it was torpedoed by a German U-Boat off the coast of Britain on February 5th, 1918. The boat sunk, taking 33 of Ed’s fellow Company F, 6th Battalion, 20th Engineer comrades with her. The 6th Battalion lost 95 men that day. Luckily, Ed was one of survivors.

This post is dedicated to the 20th Engineers and my continued interest in the unit. For more info on the 20th Engineers and the idea of forestry units in wartime, please check out The Forest History Society’s website here: http://www.foresthistory.org/research/WWI_ForestryEngineers.htm

Ed’s book is filled with plenty of wonderful tidbits about the 20th Engineers during WWI as well as a series of funny cartoons and sketches done to help illustrate the book. Here are a few of my favorites:

WWI Photo – Wounded 32nd Division Captain Poses in Paris Studio on Christmas 1918

Wounded soldier photos are some of the hardest photos to find in the collecting field. Often times a collector will come across a photo of a veteran wearing a wound chevron, or occasionally a shot of a soldier with a cane. In this case, I was able to pick up a grouping of photos taken at a Paris photo studio showing an assortment of wounded vets who recently were treated at a local Paris hospital. They hobbled over to a studio on Christmas day of 1918 to have their photos taken. These shots were some of the most expensive I’ve ever purchased, but they were well worth the investment. This is the more subdued of the four photos, but took me a long time to research and I wanted to post it for the internet community.

I was tipped off by a Dutch friend of mine (thanks Rogier!) that his photo may be of a Dutch-American given his last name of Haan. Starting with the basic ancestry.com search of a name and hometown I was able to find a few bits of info. His name was Albert Haan and was born in 1893. I had to search a bit to find the census records for him, as they were listed under a misinterpreted/transcribed name of Hoan. Anyway it appears that Albert became an Army informant for the Veterans Association after the war. He is listed in a 1922 court case where he (and another veteran from my photo grouping) is listed as an informant. Anway, he is listed as being employed by the US Army in the 1920 Census and is shown as having a wife named Frances L and a daughter named Frances L. His daughter was only 2 months old at the time of the census. His wife appear to have been born around the turn of the century. He is listed as having been born in Holland in his earlier census entry, but mysteriously switched his place of birth to Michigan in the 1910 and 1920 census. He must’ve been able to hide his accent! (7/9/2023 Edit – after further research it appears that he was born in Grand Rapids, MI)

His Veterans Affairs death file lists the following:

| Name: | Albert Haan |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Birth Date: | 12 Mar 1893 |

| Death Date: | 30 Nov 1986 |

| SSN: | 234014340 |

| Enlistment Date 1: | 13 May 1910 |

| Release Date 1: | 12 Mar 1914 |

| Enlistment Date 2: | 15 Jul 1917 |

| Release Date 2: | 24 May 1920 |

Sounds like he served early in 1910 and was released in 1914. He likely served with the Michigan National Guard at this point. He re-enlisted in 1917 and served until may of 1920 with the Army.

He had one daughter named Frances who was born in Washington D.C. in 1920. Albert was shipped back to the States in 1919 and was busy rehabilitating at Walter Reed Hospital between 1919 and 1920. Sounds like he had at least one “special visit”. He also had a son named Carl in 1922 while living in Washington D.C.

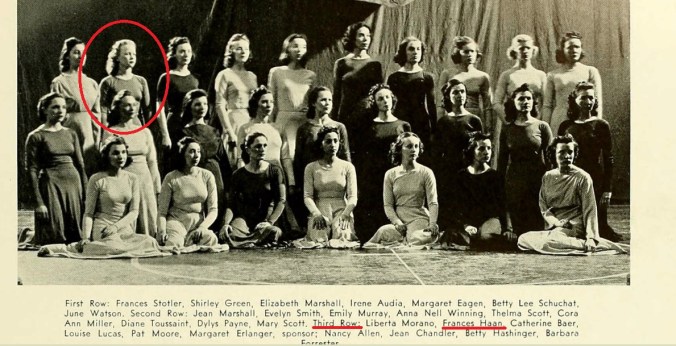

At some point the family moved from Washington D.C. to West Virgina where they apparently spent the rest of their lives. The daughter, Frances Louise Haan appears in the 1939 and 1940 University of West Virginia yearbooks and can be seen below. Quite the stunner for 1940!

I wonder if Frances is still alive? I can’t find any info on her past 1941. Ancestry.com has no information regarding her marriage or future life. She may still be alive and may be able to shed some light onto her father’s war service. I hope a family member finds this post!

Carl J Haan is harder to track down. I do know he enlisted for the US Army in July of 1942. He was surprisingly listed as an actor as a profession! This is the first time I’ve seen this!

| Name: | Carl J Haan |

|---|---|

| Birth Year: | 1922 |

| Race: | White, citizen (White) |

| Nativity State or Country: | Dist of Columbia |

| State of Residence: | West Virginia |

| County or City: | Kanawha |

| Enlistment Date: | 1 Jul 1942 |

| Enlistment State: | Kentucky |

| Enlistment City: | Fort Thomas Newport |

| Branch: | Branch Immaterial – Warrant Officers, USA |

| Branch Code: | Branch Immaterial – Warrant Officers, USA |

| Grade: | Private |

| Grade Code: | Private |

| Term of Enlistment: | Enlistment for the duration of the War or other emergency, plus six months, subject to the discretion of the President or otherwise according to law |

| Component: | Army of the United States – includes the following: Voluntary enlistments effective December 8, 1941 and thereafter; One year enlistments of National Guardsman whose State enlistment expires while in the Federal Service; Officers appointed in the Army of |

| Source: | Civil Life |

| Education: | 2 years of college |

| Civil Occupation: | Actors and actresses |

| Marital Status: | Single, without dependents |

| Height: | 70 |

| Weight: | 168 |

Amazingly he served in the US Army Air Force in WWII, Korea, and Vietnam! Quite the lineage! This family continues to surprise me. Sadly he passed away on March 22nd, 2000 and is buried in Cameron Memory Gardens in Cameron, MO. His wife Eleanor passed away in 2002.

| Name: | Carl J. Haan | |

|---|---|---|

| SSN: | 232-24-6283 | |

| Last Residence: | 64469 Maysville, Dekalb, Missouri, United States of America | |

| Born: | 4 Apr 1922 | |

| Died: | 22 Mar 2000 | |

| State (Year) SSN issued: | North Carolina or West Virginia (Before 1951) | |

WWII Pacific Theater of War in Color: Curtiss SC Seahawk Scout seaplane in Vibrant Color! 1944

The Curtis SC Seahawk was a scout aircraft designed by the Curtiss Aeroplane Company for use in the Pacific Theater of Operations in 1944. Only 577 were built and these planes are rarely seen in color, especially while stationed overseas. Some experts argue that this was the best US float plane used during WWII.

This photo was snapped by a Navy fighter pilot in 1945 on Guam. The original color slide is now in my collection. A rare addition!

Here are some internet facts I found about the SC-1:http://www.usslittlerock.org/Armament/SC-1_Aircraft.html

The Aircraft

The Curtiss SC-1 Seahawk was designed to meet the need for a reconnaissance seaplane that could be launched from US Navy battleships and cruisers. Designed as a single-seat aircraft the SC-1 could theoretically hold its’ own against enemy fighters.

The SC-1 was the last of the scout observation types and was the most highly developed with vastly improved performance over earlier types. Power, range and armament had doubled its usefulness. It was highly maneuverable, had two forward firing .50 cal. guns, large flaps and automatic leading edge slats for improved slow speed characteristics, and radar carried on the underside of the starboard wing proved highly successful during search missions. Space needed aboard ship was minimized by folding the wings back manually, making the overall width equal to the span of the horizontal tail surfaces.

Built in Columbus, Ohio, the SC-1 was initially fitted out with a fixed wheel undercarriage, then was ferried to Naval bases, where floats were attached.

The SC-1 was liked by some pilots and disliked by others, but generally well accepted. It could out climb an F6F “Hellcat” to 6,000 ft. and out-turn the F8F “Bearcat”.

Losses with the “Seahawk” were high, caused mostly by the extremely hazardous conditions in which they operated. With too hard a water landing the engine would drop, the propeller cutting through the float. Several mishaps occurred due to a faulty auto-pilot system. Aircraft and pilots were lost due to unknown landing accidents. It wasn’t until one pilot “walked away”, that it was discovered that the auto-pilot was taking over on landings. As a result, all automatic pilot systems were made inoperative on all SC’s. (For more information see U.S.S. Little Rock “Collision at Sea and other Underway Hazards” page.)

During the height of their career, crews aboard ship looked with pleasure at the “Seahawks” aft on the catapults as their “Quarterdeck Messerschmitts”.

The SC-1 first flew in February 1944 and 950 were ordered, later decreased to 566 because of the Victory in the Pacific. It continued in service for a number of years after the war as trainers, eventually being replaced by helicopters.

(Click drawing for a larger view)

WWII in Color: Invasion of Guam, July 1944 Caught on Film in Color from the Skies Over Guam

Shot from the cockpit of a F6F-3 Hellcat flown by Edward W. Simpson Jr. of the VF-35, this incredible set of images depicts the opening few hours of the infamous Invasion of Guam. Simpson carried his Kodak 35mm camera loaded with color film during many of the key battles of the Pacific, and PortraitsofWar has been lucky enough to acquire the entire collection. In this installment, I’ve scanned a series of shots taken during the Guam invasion. Many are identified as to location and were verbally described on a cassette tape that accompanied the collection.

Orote Peninsula

Source: http://www.pacificwrecks.com/airfields/marianas/orote/index.html

Location

Located the western shore of Guam on the Orote Peninsula, bordering Apra Harbor to the north and Sumay to the west, and Agat Bay to the south. Orote was known as Guamu Dai Ichi (Guam No. 1) by the Japanese.

Construction

Built prior to the war, by the US Marine Corps detachment of 10 officers and 90 enlisted men when they arrived in Guam on March 17, 1921. The Marine unit constructed an air station near the water at Sumay village, including a hangar for their amphibious aircraft. In 1926, a new administration office was constructed which housed the squadron offices, sick bay, dental office, aerological office and guardhouse. In early 1927, the squadron departed for Olongapo. Only a handful of men remained here until September 23, 1928, when Patrol Squadron 3-M, consisting of 85 enlisted men and 4 to 6 officers, was assigned to Guam. Shortly thereafter, the naval air station was closed on February 24, 1931, as a cost-saving measure.

Japanese Occupation

When the Japanese attacked Guam, they did not bomb the abandoned naval air station. When they occupied the area, they constructed Orote Field, using Korean and Guamian labor, and used the base until the liberation of Guam.

Used by the Japanese navy from April 1944 to June 1944. As of June 1, 1944, Japanese air strength on Guam consisted of 100 Zeros and 10 J1N1 Irvings at Airfield #1 and 60 Ginga at Airfield #2.

American Neutralization

On February 23, 1944, American carrier based airplanes attacked the field, and other American raids soon followed. During the Battle of the Philippine Sea the field was used by the Japanese carrier-based airplanes to refuel and rearm. The Japanese airplanes based at Orote Field were also used to attack the American fleet. American raids on June 19, 1944 destroyed the landing fields, the aircraft on the ground and such aircraft that managed to take off. American pilots reported extremely intense antiaircraft fire around Orote Field. Fifteen Japanese airplanes crashed at Orote Field on June 19, 1944.

On June 20, 1944, numerous actions occurred in the immediate vicinity of Orote Field between American carrier airplanes and Japanese aircraft seeking refuge at Orote Field after flying from their carriers, or Japanese refueling and rearming to attack American carriers. Numerous dogfights took place in the air above Orote Field and numerous strikes by American airplanes destroyed Japanese facilities and airplanes on the ground. This denied the Japanese extensive use of this crucial airfield during the battle.

Land Battle at Orote

The Japanese assigned the defense of Orote Peninsula to the 54th Independent Guard Unit under command of Air Group Commander Asaichi Tamai. After American invasion on July 21, 1944, the 1st Provincial Marine Brigade under command of Lt. General Lemuel C. Shepherd fought its way through the Agat village to the base of Orote Peninsula. Here the Japanese had constructed an elaborate interlocking system of pillboxes, strong points and trenches.

Regiments of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, the 4th and 22nd, fought their way through the area. Shortly before midnight on July 26, 1944, the Japanese trapped on the peninsula staged a suicide attack and were completely wiped out. The advancing Marines still met heavy Japanese resistance in the vicinity of the airfield, where the Japanese fought from caves and coconut bunkers. The peninsula was declared secure on July 29, 1944. It is estimated that the Japanese lost more than 3,000 men defending Orote Peninsula.

Several Japanese aircraft wrecks were captured at the airfield, including G4M2 Betty 2095 , G4M2 Betty 12013 and J1N1 Irving.

American Use

Immediately put into use by Marine air power for close support missions during the liberation of Guam. This was accomplished by Marine Air Group (MAG) 21. By mid-November 1944, MAG-21, now commanded by Colonel Edward B. Carney, was an oversized group, having 12 squadrons based at Orote Field, 529 officers, 3,778 enlisted men and 204 aircraft. MAG-21 was shifted to Agana Airfield in 1945, as Orote Field had always been hampered by adverse crosswinds. The field was then used by the US Navy for repairing damaged aircraft.

American Units Base at Orote

VF-76 (F6F) September 1944

MAG 21 (F4U) July, 1944 – to Agana in 1945

USS Santee (F6F) landed at Orote August 1944

Today

Orote Field was finally closed to all but emergency landings in 1946. Today, the cross-runway is used for C-130 touch-and-go flight training, and for helio-ops by Navy Seals. Much of the time the airfield is off-limits. The major runway runs from NW to SE and the secondary runway crosses the first and runs in a NE to SW direction. Limited tours of the airfield are available.

References

Thanks to Jennings Bunn and Jim Long for additional information.

WWII Color Slide Photo – Aerial Shot of the Opening Hour of the Battle of Tarawa Shot by Carrier Fighter Pilot

Talk about rare! A recent color slide collection has provided a rare glimpse into the opening hours of the infamous Battle of Tarawa. A Navy carrier-based fighter pilot snapped this 35mm color slide while flying cover over Betio on that fateful day on November 20th, 1943. I’ve never personally seen a color shot taken from the air during this battle. The series I recently acquired may be some of the only known color aerial shots taken during the opening hours of the battle. And the kicker is that I digitized the veteran’s audio cassette tape describing the image.

Collectors Note: The best thing about collecting 35mm color and B/W negatives/slides is that they were physically present during the event. Photographs were printed afterwards, but nitrate and celluloid negatives were physically processed through the camera during the event.

Please forward to 3:45 for a verbal description of the slide by the veteran who snapped the image

And some info on the opening day of the Battle of Tarawa (from Wikipedia):

The Battle of Tarawa (US code name Operation Galvanic) was a battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II, largely fought from November 20 to November 23, 1943. It was the first American offensive in the critical central Pacific region.

It was also the first time in the war that the United States faced serious Japanese opposition to an amphibious landing. Previous landings met little or no initial resistance. The 4,500 Japanese defenders were well-supplied and well-prepared, and they fought almost to the last man, exacting a heavy toll on the United States Marine Corps. The US had suffered similar casualties in other campaigns, for example over the six months in the campaign for Guadalcanal, but in this case the losses were suffered within the space of 76 hours. Nearly 6,000 Japanese and Americans died on the tiny island in the fighting.[2]

Background

In order to set up forward air bases capable of supporting operations across the mid-Pacific, to the Philippines, and into Japan, the U.S. needed to take the Marianas Islands. The Marianas were heavily defended. Naval doctrine of the time held that in order for attacks to succeed, land-based aircraft would be required to weaken defenses and provide some measure of protection for the invasion forces. The nearest islands capable of supporting such an effort were the Marshall Islands, northeast of Guadalcanal. Taking the Marshalls would provide the base needed to launch an offensive on the Marianas but the Marshalls were cut off from direct communications with Hawaii by a garrison and air base on the small island of Betio, on the western side of Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands. Thus, to eventually launch an invasion of the Marianas, the battles had to start far to the east, at Tarawa.

Following the completion of their campaign on Guadalcanal, the 2nd Marine Division had been withdrawn to New Zealand for rest and recuperation. Losses were replaced and the men given a chance to recover from the malaria and other illnesses that weakened them through the fighting in the Solomons. On July 20, 1943 the Joint Chiefs directed Admiral Chester Nimitz to prepare plans for an offensive operation in the Gilbert Islands. In August Admiral Raymond Spruance was flown down to New Zealand to meet with the new commander of the 2nd Marine Division, General Julian Smith, and initiate the planning of the invasion with the division’s commanders.

Located about 2,400 miles southwest of Pearl Harbor, Betio is the largest island in the Tarawa Atoll. The small, flat island lies at the southern most reach of the lagoon, and was home to the bulk of the Japanese defenders. Shaped roughly like a long, thin triangle, the tiny island is approximately two miles long. It is narrow, being only 800 yards wide at the widest point. A long pier was constructed from the north shore from which cargo ships could unload out past the shallows while at anchor in the protection of the lagoon. The northern coast of the island faces into the lagoon, while the southern and western sides face the deep waters of the open ocean.

Following Carlson’s diversionary Makin Island raid of August 1942, the Japanese command was made aware of the vulnerability and strategic significance of the Gilbert Islands. The 6th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force arrived to reinforce the island in February 1943. In command was Rear Admiral Tomanari Sichero, an experienced engineer who directed the construction of the sophisticated defensive structures on Betio. Upon their arrival the 6th Yokosuka became a garrison force, and the unit’s identification was changed to the 3rd Special Base Defense Force. Sichero’s primary goal in the Japanese defensive scheme was to stop the attackers in the water or pin them on the beaches. A tremendous number of pill boxes and firing pits were constructed with excellent fields of fire over the water and sandy shore. In the interior of the island was the command post and a number of large shelters designed to protect defenders from air attack and bombardment. The island’s defenses were not set up for a battle in depth across the island’s interior. The interior structures were large and vented, but did not have firing ports. Defenders in them were limited to firing from the doorways.[3]

The Japanese worked intensely for nearly a year to fortify the island.[4] To aid the garrison in the construction of the defenses, the 1,247 men of the 111th Pioneers, similar to the Seabees of the U.S. Navy, along with the 970 men of the Fourth Fleet’s construction battalion were brought in. Approximately 1,200 of the men in these two groups were Korean forced laborers. The garrison itself was made up of forces of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Special Naval Landing Force was the marine component of the IJN, and were known by US intelligence to be more highly trained, better disciplined, more tenacious and to have better small unit leadership than comparable units of the Imperial Japanese Army. The 3rd Special Base Defense Force assigned to Tarawa had a strength of 1,112 men. They were reinforced by the 7th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force, with a strength of 1,497 men. It was commanded by Commander Takeo Sugai. This unit was bolstered by 14 Type 95 light tanks under the command of Ensign Ohtani.

A series of fourteen coastal defense guns, including four large Vickers 8-inch guns purchased during the Russo-Japanese War from the British,[2] were secured in concrete bunkers and located around the island to guard the open water and the approaches into the lagoon. It was thought these big guns would make it very difficult for a landing force to enter the lagoon and attack the island from the north side. The island had a total of 500 pillboxes or “stockades” built from logs and sand, many of which were reinforced with cement. Forty artillery pieces were scattered around the island in various reinforced firing pits. An airfield was cut into the bush straight down the center of the island. Trenches connected all points of the island, allowing troops to move where needed under cover. As the command believed their coastal guns would protect the approaches into the lagoon, an attack on the island was anticipated to come from the open waters of the western or southern beaches. Kaigun Shōshō Keiji Shibazaki, an experienced combat officer from the campaigns in China relieved Sichero in July 20, 1943 in anticipation of the coming combat. Shibazaki continued the defensive preparations right up to the day of the invasion. He encouraged his troops, saying “it would take one million men one hundred years” to conquer Tarawa.

November 20

Marines seek cover amongst the dead and wounded behind the sea wall on Red Beach 3, Tarawa.

The American invasion force to the Gilberts was the largest yet assembled for a single operation in the Pacific, consisting of 17 aircraft carriers (6 CVs, 5 CVLs, and 6 CVEs), 12 battleships, 8 heavy cruisers, 4 light cruisers, 66 destroyers, and 36 transport ships. On board the transports was the 2nd Marine Division and a part of the army’s 27th Infantry Division, for a total of about 35,000 troops.

As the invasion flotilla hove to in the predawn hours, the islands four 8 inch guns opened fire on the task force. A gunnery duel soon developed as the main batteries on the battleships Colorado and Maryland commenced a counter-battery fire. The counter-battery proved accurate, with several of the 16 inch shells finding their mark. One shell penetrated the ammunition storage for one of the guns, igniting a huge explosion as the ordnance went up in a massive fireball. Three of the four guns were knocked out in short order. Though all four guns fell silent, one continued intermittent, though inaccurate, fire through the second day. The damage to the big guns left the approach to the lagoon open. It was one of the few successes of the naval bombardment.

Following the gunnery duel and an air attack of the island at 0610, the naval bombardment of the island began in earnest and was sustained for the next three hours. Two mine sweepers with two destroyers to provide covering fire entered the lagoon in the pre-dawn hours and cleared the shallows of mines.[5] A guide light from one of the sweepers then guided the landing craft into the lagoon where they awaited the end of the bombardment. The plan was to land Marines on the north beaches, divided into three sections: Red Beach 1 to the far west of the island, Red Beach 2 in the center just west of the pier, and Red Beach 3 to the east of the pier. Green Beach was a contingency landing beach on the western shoreline and was used for the D+1 landings. Black Beaches 1 and 2 made up the southern shore of the island and were not used. The airstrip, running roughly east-west, divided the island into north and south.

U.S. Coast Guardsmen ferrying supplies pass an LCM-3 which has taken a direct hit at Tarawa.

The Marines started their attack from the lagoon at 09:00, thirty minutes later than expected, but found the tide had still not risen enough to allow their shallow draft Higgins boats to clear the reef. Marine battle planners had not allowed for Betio’s neap tide and expected the normal rising tide to provide a water depth of 5 feet (1.5 m) over the reef, allowing larger landing craft, with drafts of at least four feet (1.2 m), to pass with room to spare. But that day and the next, in the words of some observers, “the ocean just sat there,” leaving a mean depth of three feet (0.9 m) over the reef. (The neap tide phenomenon occurs twice a month when the moon is near its first or last quarter, because the countering tug of the sun causes water levels to deviate less. But for two days the moon was at its farthest point from earth and exerted even less pull, leaving the waters relatively undisturbed.)

At 0900 the supporting naval bombardment was lifted to allow the Marines to land. The reef proved a daunting obstacle. Only the tracked LVT “Alligators” were able to get across. The Higgins boats, at four feet draft, were unable to clear the reef.[6] With the pause in the naval bombardment those Japanese that survived the shelling dusted themselves off and manned their firing pits. Japanese troops from the southern beaches were shifted up to the northern beaches. As the LVTs made their way over the reef and in to the shallows the number of Japanese troops in the firing pits slowly began to increase, and the amount of combined arms fire the LVTs faced gradually intensified. The LVTs had a myriad of holes punched through their non-armored hulls, and many were knocked out of the battle. Those ‘Alligators’ that did make it in proved unable to clear the sea wall, leaving the men in the first assault waves pinned down against the log wall along the beach. A number of ‘Alligators’ went back out to the reef in an attempt to carry in the men who were stuck there, but most of these LVTs were too badly holed to remain sea worthy, leaving the marines stuck on the reef some 500 yards (460 m) off shore. Half of the LVTs were knocked out of action by the end of the first day.

Colonel David Shoup was the senior officer of the landed forces, and he assumed command of all landed Marine Corps troops upon his arrival on shore. Although wounded by an exploding shell soon after landing at the pier, Colonel Shoup took charge of the situation, cleared the pier of Japanese snipers and rallied the first wave of Marines who had become pinned down behind the limited protection of the sea wall. During the next two days, working without rest and under constant withering enemy fire, he directed attacks against strongly defended Japanese positions, pushing forward despite daunting defensive obstructions and heavy fire. Throughout Colonel Shoup was repeatedly exposed to Japanese small arms and artillery fire, inspiring the forces under his command. For his actions on Betio he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Several early attempts to land tanks for close support and to get past the sea wall failed when the landing craft carrying them were hit on their run into the beach and either sank outright or had to withdraw while taking on water. Two Stuart tanks eventually landed on the east end of the beach but were knocked out of action fairly quickly. Three medium Sherman tanks were landed on the western end of the island and proved considerably more effective. They helped push the line in to about 300 yards (270 m) from shore. One became stuck in a tank trap and another was knocked out by a magnetic mine. The remaining tank took a shell hit to its barrel and had its 75 mm gun disabled. It was used as a portable machine gun pillbox for the rest of the day. A third platoon was able to land all four of its tanks on Red 3 around noon and operated them successfully for much of the day, but by day’s end only one tank was still in action.

By noon the Marines had successfully taken the beach as far as the first line of Japanese defenses. By 15:30 the line had moved inland in places but was still generally along the first line of defenses. The arrival of the tanks started the line moving on Red 3 and the end of Red 2 (the right flank, as viewed from the north), and by nightfall the line was about half-way across the island, only a short distance from the main runway.

The communication lines which the Japanese installed on the island had been laid shallow and were destroyed in the naval bombardment, effectively preventing commander Keiji Shibazaki’s direct control of his troops. In mid-afternoon he and his staff abandoned the command post at the west end of the airfield, to allow it to be used to shelter and care for the wounded, and prepared to move to the south side of the island. He had ordered two of his Type 95 light tanks to act as a protective cover for the move, but a 5″ naval high explosive round exploded in the midst of his headquarters personnel as they were assembled outside the central concrete command post, resulting in the death of the commander and most of his staff. This loss further complicated Japanese command problems.[7][8]

As night fell on the first day the Japanese defenders kept up a sporadic harassing fire, but did not launch an attack on the Marines clinging to their beachhead and the territory won in the day’s hard fighting. With Rear Admiral Shibazaki killed and their communication lines torn up, each Japanese unit was essentially acting in isolation, and indeed had been since the commencement of the naval bombardment. The Marines brought a battery of 75 mm Pack Howitzers ashore, unpacked them and set them up for action for the next day’s fight, but the bulk of the second wave was unable to land. They spent the night floating out in the lagoon without food or water, trying to sleep in their Higgins boats. A number of Japanese marines slipped away in the night, swimming out to a number of the wrecked LVTs in the lagoon, and also to the Niminoa, a wrecked steamship lying west of the main pier. There they laid in wait for dawn, when they would fire upon the US forces from behind. The long night dragged on, but lacking central direction, the Japanese were unable to coordinate for a counterattack against the toe hold the Marines held on the island. The feared counterattack never came and the Marines held their ground. By the end of the first day, of the 5,000 Marines put ashore, 1,500 were casualties, either dead or wounded.